Introduction

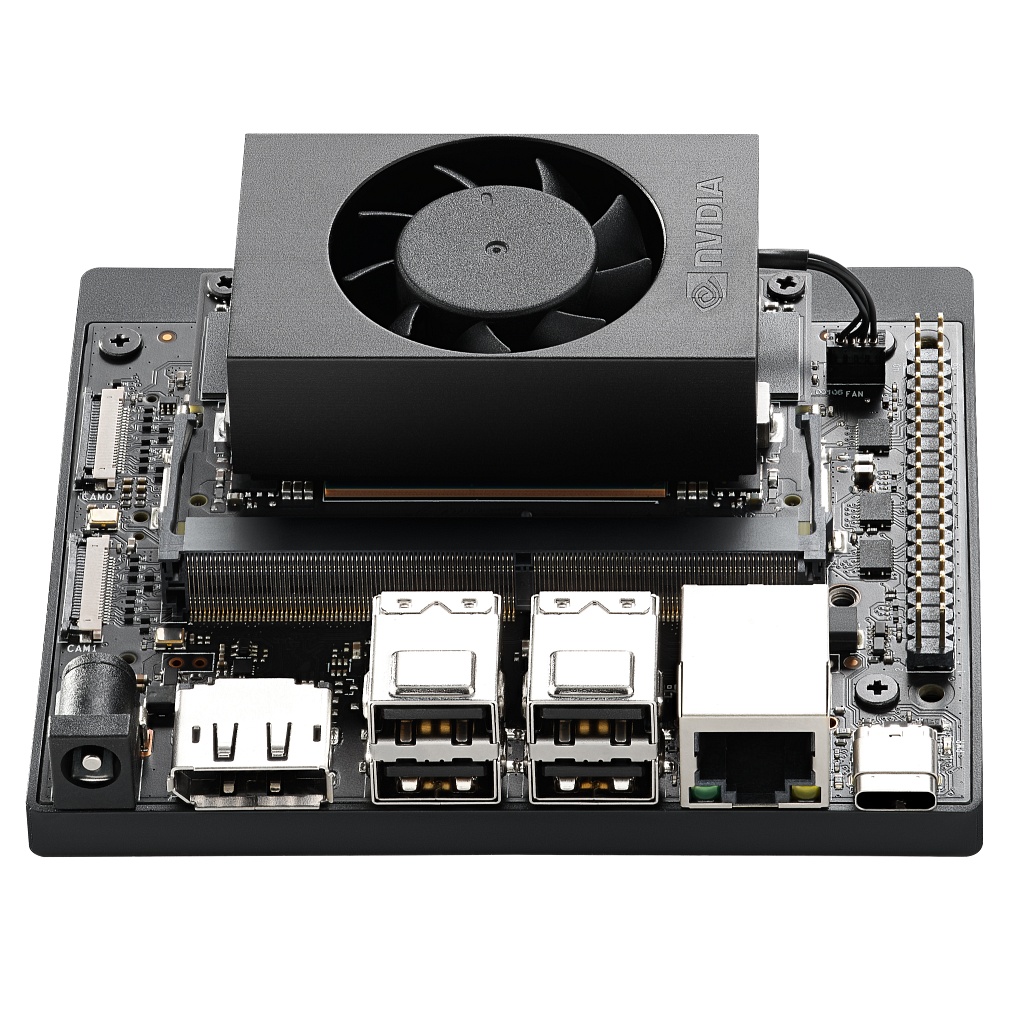

The NVIDIA® Jetson Orin Nano™ Developer Kit sets a new standard for creating entry-level AI-powered robots, smart drones, and intelligent cameras, and simplifies getting started with the Jetson Orin Nano series.

The included carrier board can also be used to test and develop with separately sold Jetson Orin NX modules.

About this Document

This user guide document provides detailed information on how you can use the developer kit both from a hardware and a software perspective.

For quickly getting started with the developer kit, please refer to Getting Started with NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano Developer Kit .

Additional Documentations

- Getting Started with NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano Developer Kit

- NVIDIA Jetson Linux Developer Guide

- NVIDIA SDK Manager Documentation

- Jetson Download Center