A Highland Song is the new game from Inkle, the famous storyteller responsible for Heaven’s Vault, 80 Days, Overboard!, Pendragon and the Sorcery! adaptations. And for this adventure, the genre has changed again. It’s still a narrative game at heart, but it’s wrapped in a platforming shell. You play as a young woman called Moira who longs to see the sea and so flees her home and into – and beyond – the Scottish Highlands in pursuit of it. You control her by running, jumping, and climbing, and at times do so to the beat of folk music that erupts sporadically from the game.

It’s a game inspired, I believe, by the real-life walking adventures of Inkle co-founder Joseph Humfrey, who was once lost in the Highlands. But it is also inspired by the many literary people who have tried to capture the magic of the Highlands and the march, over many, many years. In this piece, Christian Donlan and I play along and talk about our experiences.

A Highland Song is coming to PC and Nintendo Switch “soon” – likely sometime this year, although that hasn’t been confirmed.

Chris: I don’t want to start on too heavy a note, but about 10 years ago when I was diagnosed with MS, I was really worried that my mobility days were numbered. I started really looking for games about the pleasures of movement – games like Crackdown and the original Tomb Raiders, which thought they were mostly about what it’s like to run and jump and all that jazz. I think I would have jumped at the chance to play something like Highland Song.

I was very lucky, and 10 years later, I still wobble on my feet, and if I walk even more now, and I am more attentive to what it feels like to walk, to its particular qualities. So it makes me really curious to play a game that revolves around that. Do you think that’s a fair way to categorize this game? Is that part of what you think Inkle means here?

A Highland Song very well captures this deep feeling of being among something ancient and massive.

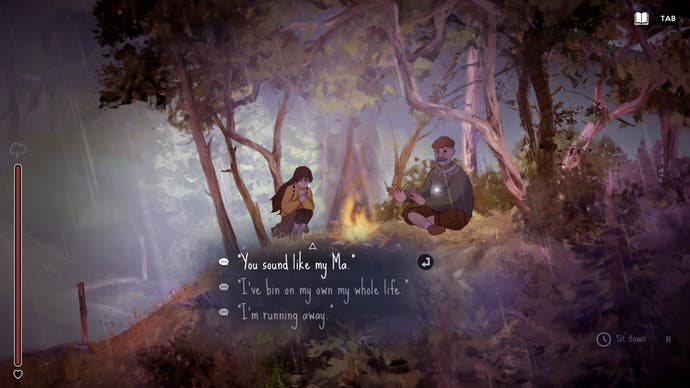

Bertie: I think it’s absolutely about the joy of moving and moving. One game that really reminds me, actually, is Mario, in the way you pick up speed as you run in one direction, and the way the game wants you to jump over obstacles – like the thing the more important was unimpeded flow and rhythm. I guess it also has to do with the game’s connection to the music.

I’ll explain quickly: there are times in the game, usually when you’re rolling down a big hill (and often following a deer), where the game turns into music, folk music, and you’re challenged to push buttons in time with her to, I’m not sure, keep the flow going? Looks like it’s a mechanic you use to cover great distances or climb giant inclines. And I think the thinking behind it is the lyricism and the feeling of wild abandon you get when running up hills like these – not that I’ve ever run up a hill. Why should I do it?

But it seems like a tough game to grasp in terms of what it’s really about, if that makes sense?

Chris: YES! And the more I play, the more I like it. So it’s a starting game on foot through hills and mountains, but the journey still gives you those choices. It starts out looking like a classic left or right thing, but then you have all those moments where you can move around the screen, so to speak, jumping from one 2D plane to another. Along with this there are rock climbing sections and even a bit of caving. A move of one type turns into another, then I collected items and found new map pieces, and stopped to rest, conserve energy, and shelter from the rain.

What I mean is there’s a bunch of stuff going on, a bunch of systems that seem very elegantly channeled by the player deciding where to go next. And after playing quite a bit, I have this nice giddy feeling of not knowing the limits of the game and what’s possible here.

Can I quickly say one thing about flatness? The game has this extraordinary kind of rugged flatness. You climb those mountain slopes in 2D, but after a few minutes I really feel like I get a sense of the moving earth through my fingers and hands. And when you just switch shots and go from foreground to background, to a mountain that I kind of assumed was just a backdrop, there’s this magical confusion of 2D and 3D space. For some: I am deliciously lost in this game. Do you feel lost?

Bertie: Ha ha – absolutely! It’s misleading, isn’t it? It doesn’t seem like it should be very hard – although hard isn’t the right word; it doesn’t seem like it should be very complicated, since he’s so overtly friendly in his appearance and bubbly in character. And yet there’s a kind of very natural impenetrability to hills or mountains – I don’t know how you classify them but they’re big, in an intimidating way. And I love that the only way to navigate them is with scribbled maps or – and I especially love this – folklore. Using the kind of natural wisdom passed down from generation to generation.

And it is this connection with a lineage as long and wide as the mountains or the hills themselves that captivates me. That there were people in those areas who walked those hills and mountains, building a respectful relationship with them, for countless years before me. How many people have had similar adventures here, or similar thoughts looking at the night sky?

You mentioned that, but I love how the game also wows you with elemental effects, like cold, rain, and wind, and how you feel so small and vulnerable because of them. It might seem like a silly question, but does the game make you feel a bit like what it would be like to actually be out there on those hills?

Chris: Absolutely! But somehow mediated, through the flatness, the animation, the sense of living paint that brought the mountains and the world to life, to the fact that you can still see individual brushstrokes in places?

I tend to think of Inkle as sort of literary at heart, and wonder how much that game was inspired by something like Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain. It’s this short but incredibly rich book about the Cairngorms, exploring them, discovering them, living around them. And it feels a lot like that, not just the Scottishness and caring for nature, but that feeling of approaching a place from so many angles and just being slightly lost in something much bigger ?

On that note, and to sort of wrap up, you know Inkle way better than I do. Do you see a lot of classic Inkle in there? From what I can see, it sounds like a feeling that they’re simultaneously taking their ideas and moving away from them while boiling something down to its richest expression? It’s a new direction, but there’s a core that feels classically Inkle?

Bertie: Oh, absolutely. I interviewed the founders of Inkle not too long ago, and it’s actually Joseph Humfrey’s experience of getting lost in the Highlands that I think this game is based on. But it is also, as you said, absolutely literary. I remember fellow co-founder Jon Ingold talking about how they struggled to convey the magic of something like walking through a game, and how they sought out literary references to help do that.

But yeah, one of the hallmarks of Inkle as I see it is elegance in simplicity and the removal of anything unnecessary – and maybe that’s what’s wrong, initially, about what’s here. It’s kind of like a trifle that you thought was just cream to begin with, then you dove in and found a whole lot more there. So much so that a, I really want to eat a little now, and b, I’m mightily intrigued to find out what else A Highland Song has to say.

To view this content, please enable targeting cookies. Manage cookie settings

Article source https://www.eurogamer.net/a-highland-song-captures-the-joys-and-dangers-of-being-lost-in-nature